Original Analysis at: https://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/africa-versus-coronavirus-four-much-needed-capabilities

For many African countries, prevention of Coronavirus has no alterative as financial and structural demands of treatment far exceed capabilities. Without stricter measures, the infection curve will be exponential and flattening it will take a long time with more deaths.

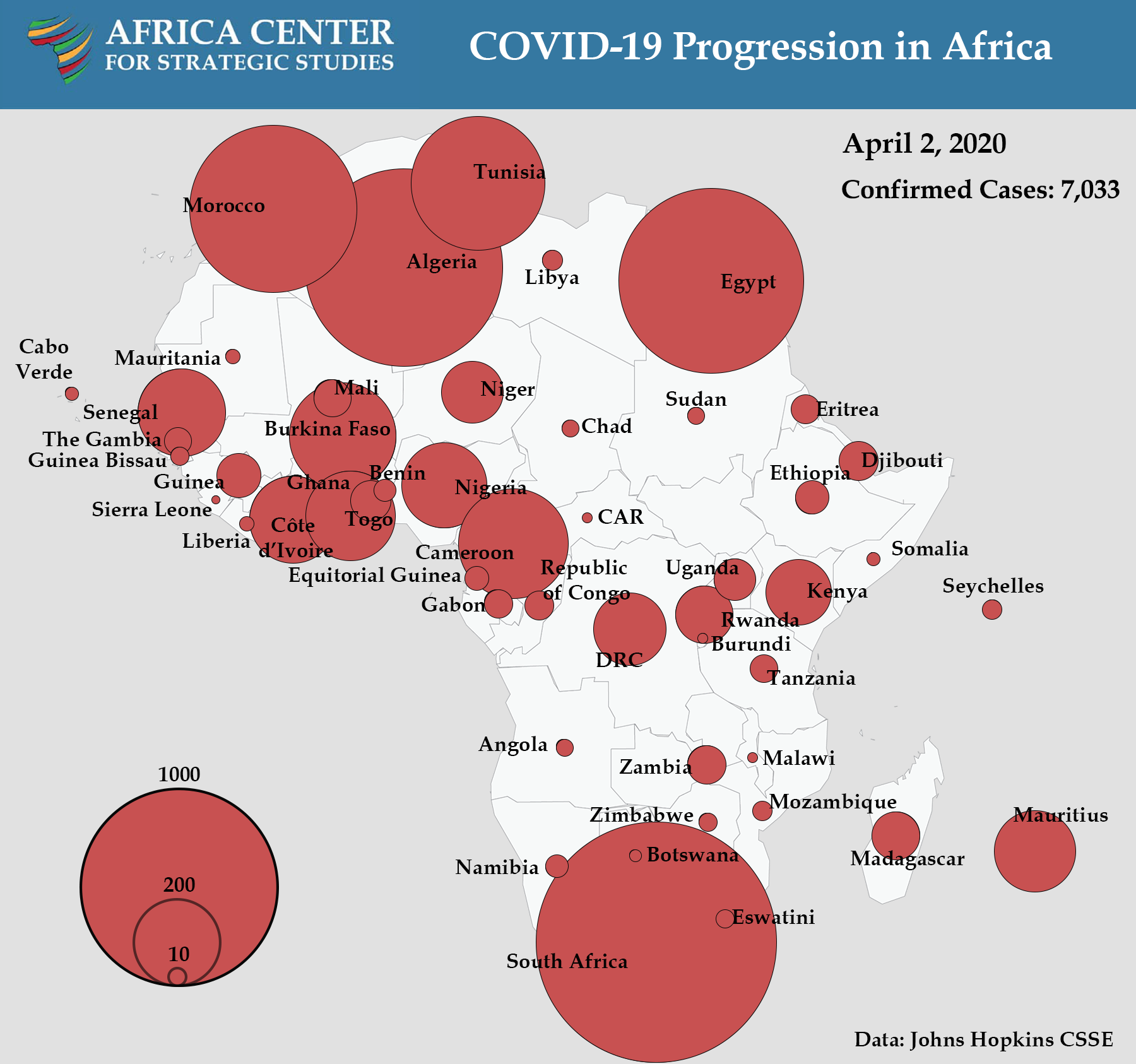

The spread of Coronavirus, COVID-19, has now hit almost all African countries with over 10,000 confirmed cases in all African countries. (1) According to the latest data by the Africa Center for Disease Control, the breakdown remains fluid as countries confirm cases as and when. The 1.2 billion-people continent of Africa has rising cases with a handful of countries holding out. Nigeria was the first sub-Saharan country to report a COVID-19 case February 27. By April 2 of Africa’s 54 countries, only four have yet to report a case of the virus: Comoros, Lesotho, Sao Tome and Principe and South Sudan. The global coronavirus pandemic has hit Africa and the resultant health crisis may easily turn into humanitarian and security disasters. These will worsen persistent crises caused by climate change-induced drought, terrorism and violent extremism, and epidemics like the Ebola disease.

Earlier in March, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, an Ethiopian, first African director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), called on African leaders to take seriously the threat from the virus. As he stated, “Africa should wake up, my continent should wake up.” Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning prime minister, called on G20 countries to extend Africa a $150bn aid package. (2)

Africa is also host to over 6 million refugees and 14 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), mostly in camps. (3) The camp setting with its poor health care infrastructure and low sanitation could make the spread of COVID-19 faster and its implication disastrous. With this pandemic, the danger to the lives of young irregular African migrants within and outside the continent will be increased risks to life, livelihood and safety. In this paper Mehari T. Maru professor at the European University Institute examines the numerous humanitarian needs, which should be delivered in a complex environment that creates new potentially fatal risks for aid actors and recipients particularly in the Horn of Africa. He had drafted Common African Position on Humanitarian Effectiveness and served as lead Member of the African Union High Level Advisory Group during several consultations organized by African Union Commission.

Most of the current confirmed cases are from travelers outside of the continent. The low volume of international mobility may have temporarily spared Africa the worst of the outbreak for now. However, frequent and poorly governed cross-border mobility in border areas among kin communities and pastoralists that remain outside the purview of states could make the propagation of the virus transnational.

With nearly broken public health systems, deprived public health sectors and a very small number of specialized hospitals, there is little capacity for tracing, testing, confirmation, isolation and treatment of those infected. Taking the experience of those countries already affected, the preparations and the current ICU hospitalization capacities in Africa pales in comparison to the oncoming infections. South Africa, financially better endowed than other African countries has declared the pandemic a disaster and it is employing its emergency fund. But South Africa has no more than 5,000 ICU beds that can be surpassed within the coming weeks. COVID-19 may destroy the recent gains made in African health systems.

Infection rates are expected to surge once testing is scaled up. With the increase in infection rates being confirmed, death tolls may also increase. Slower rate of infection cannot be achieved without social distancing and with a higher rate of infection, the demand for beds for treatment is expected to surge. as of April 3, the statistics have revealed various scopes of Infection over the continent: Algeria – 1,171, Angola – 8, Benin – 16, Botswana – 4, Burkina Faso – 302, Burundi – 3, Cameroon – 509, Cape Verde – 6, Central African Republic – 8, Chad – 8, Congo-Brazzaville – 41, DR Congo – 148, Djibouti – 49, Egypt – 985, Equatorial Guinea – 16, Eritrea – 22, Ethiopia – 35, Eswatini – 9, Gabon – 21, Gambia – 4, Ghana – 205, Guinea – 73, Guinea-Bissau – 15, Ivory Coast – 218, Kenya – 122, Liberia – 7, Libya – 17, Madagascar – 70, Malawi – 3, Mali – 39, Mauritania – 6, Mauritius – 186, Morocco – 791, Mozambique – 10, Namibia – 14, Niger – 120, Nigeria – 210, Rwanda – 89, Senegal – 207, Seychelles – 10, Sierra Leone – 2, Somalia – 7, South Africa – 1,505, Sudan – 10, Tanzania – 20, Togo – 40, Tunisia – 495, Uganda – 48, Zambia – 39, and Zimbabwe – 9.

Humanitarian Crises in Africa

What is more, parts of Africa, specially the Horn of Africa, are facing locust plague that devastated the plants and vegetation for humans and animals. In addition, to this pandemic, the continent is in political transition. More than 45 African countries will hold elections in 2020 and 2021. The delay and eventual conduct of the polls could trigger potential violence in relation to electoral processes and contested results. In 2016, the AU issued the Common African Position (CAP) on Humanitarian Effectiveness that enables AU, RECs and Member States to predict, prevent, respond and adapt to humanitarian challenges.(4) The CAP underlines the importance of the inextricable links between governance, development and peace and security and their positive impact on the humanitarian system.

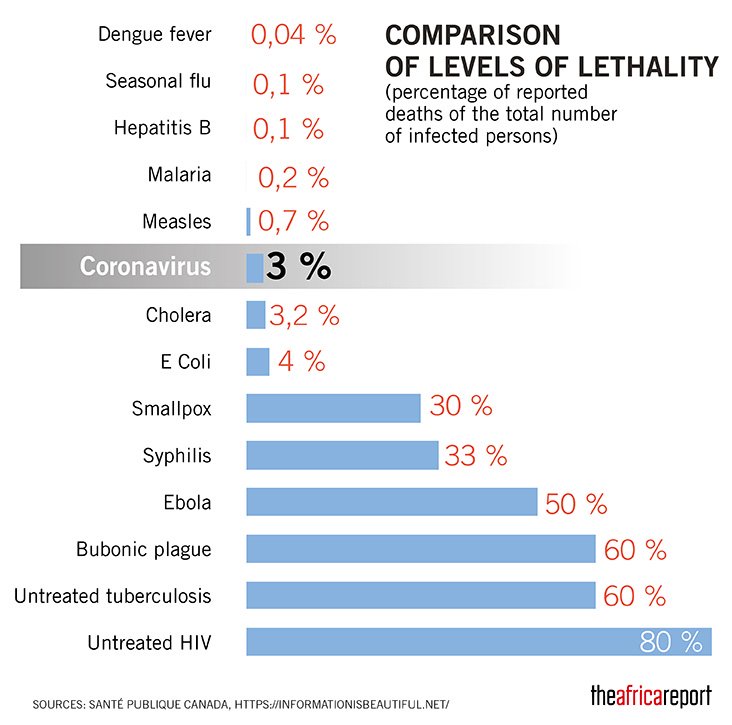

Despite lessons learned over the past decade (for example, from the management of the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa), Africa remains by far the world’s most vulnerable continent in terms of viral and bacterial infections. Though an effective means of flattening the curve of exponential COVID-19 infections, social distancing will prove difficult in Africa due communities harboring strong social culture and extended families where children are mostly taken care of by grandparents. Indeed, working in favor of Africa is its young population, with 60 percent aged below 24.

For many African countries, in the case of COVID-19 as in many other outbreaks, prevention has no alterative as financial and structural demands of treatment far exceed capabilities. Without stricter community measures such as extreme social distancing, the infection curve will be exponential and flattening it will take a long time and with it many lives. COVID-19 is no more only a health issue but could easily turn into humanitarian and security issues. Current nation-wide lockdowns, travel restrictions, shortage of supplies and stress on livelihood may surge conflicts and violence, especially in urban settings and exacerbate the current humanitarian crisis.

Recent reports indicate that the number of food insecure population in the region is currently estimated at 33 million, a 64 per cent increase from a couple years ago. (5) Nearly two million people in the region remain at risk of being affected by flooding. The desert locust invasion would put 19 million more people at risk of food insecurity in the region. (6) With the locust invasion, the number of food insecure people will double by the end of this year alone. The region remained the biggest sources and host of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). It hosts more than 4.5 million refugees, largest number of in Africa, coming mainly from South Sudan, Somalia, and Eritrea, and close to 10 million IDPs mostly in South Sudan, Somalia, Sudan and Ethiopia. (7)

| S/N | Country | Total affected population | Affected number of Children | Major factor for humanitarian situation |

| 1 | Kenya | 3.4 million | 1.6 million | Food insecurity |

| 596,045 | —————– | Refugees from other countries | ||

| 2 | Uganda | 2.4 million | 1.5 million | Food insecurity |

| 1,355,764 | 827000 | Refugees from other countries | ||

| 3 | Ethiopia | 8.5 million | 3.6 million | Food Insecurity and conflict |

| 829,925 | —————— | Refugees from other countries | ||

| 4 | Djibouti | 289,338 | 133095 | Food insecurity and refugees from other countries |

| 5 | Somalia | 6.2 million | —————– | Drought and conflict |

| 6 | South Sudan | 5 million | —————– | Food Insecurity and conflict |

| 7 | Sudan | 4.8 million | —————– | Food Insecurity and conflict |

| Total | 33,371,072 | —————– | Affected Population |

Affected African Population Summary [UNHCR]

Drought, locust invasion, protracted internal conflict and ethnic strife and the resultant displacement are the main causes for the continuing humanitarian catastrophe in the IGAD region. (8) The region extreme vulnerability to various adversities including man-made and natural disasters is most importantly an outcome of failed governance exhibited by the low state predictive, preventive and responsive capabilities. The Covid-19 pandemics hampers not only both building long-terms capabilities but also impede the provision of humanitarian response. Pandemic almost always affects both those in need of humanitarian aid, and aid workers.Affected African Population Summary [UNHCR]

AU Humanitarian Agenda

Since the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), Africa has been seized with humanitarian crises, particularly the plight of refugees, which have gravely affected the lives and livelihoods of Africans and the development of the continent. The African Union has for many years been committed to a progressive migration agenda recognizing the positive contribution of migrants to inclusive growth and sustainable development. In June 1969, the OAU adopted the Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems, that was anchored in the African culture of hospitality and solidarity as a Pan-African solution to the humanitarian crisis of refugees with a broader and more generous determination and treatment of the asylum system and refugee protection. The Arusha Conference followed this initiative on Refugees in Africa that reinforced the basic principles elaborated in the OAU Convention on Refugees. Since the Arusha conference, the OAU/AU has convened more than four high level meetings, including those in Addis Ababa in 1994, Khartoum in 1998, Banjul and Ouagadougou in 2006 and Kampala in October 2009, and extensively deliberated and produced key OAU/AU position documents and policy declarations in addressing the growing humanitarian crises on the African continent.

The global humanitarian context is characterized by a rapidly changing financial architecture and landscape, including the need for a transformative agenda for global humanitarian architecture. There is also an increased need for a new humanitarian system that is more reliable, accountable and transparent and appropriate for its purpose. The current humanitarian assistance model is based on the Framework provided through UN General Assembly Res. 46/182. Nonetheless, this humanitarian landscape has changed and there is an urgent need for its review in setting a new global agenda. The changing humanitarian landscape requires replacement of the existing humanitarian system. The CAP is one of the instruments for the development of global Humanitarian Architecture fit for its purpose and dynamic humanitarian situations in the future.

In order to address the gap in the current humanitarian system, CAP offers standpoints on which the AU’s engagement with the global system in global governance and humanitarian efficiency is to be based. It also sets substantive issues of priorities and principles applicable to Africa and achieve consensus on Africa’s key priorities, concerns and strategies. These growing and emerging challenges call for the transformation of the existing reactive humanitarian response into inclusive and responsive proactive global humanitarian architecture fit for the purpose. CAP reflects the complexity and magnitude of the humanitarian situation in Africa, including displacement, and also take African peculiarities and specific problems into account and provide African solutions to the challenges associated with humanitarian responses within the context of Pan-African solidarity. It also reiterates the importance of governance and international cooperation in responding to these causes, triggers and accelerators of humanitarian crises.

Prominence of Governance

Governance is the foundation for robust and effective humanitarian response, and for the prevention of crises. Humanitarian crises rarely led to death where there is effective, accountable governance. Drought or flood turns into large death only when there is no accountable governance. More pointedly, while displacement most often could be a consequence of famine or conflicts; and vice versa, conflict may cause, trigger or accelerate humanitarian crises such as famine and displacement either by directly causing them or impeding efforts and humanitarian aid to those in need. In addition to severe drought, locust invasions have devastated crops and pasture for livestock. In the worst affected areas, large-scale crop failure and high levels of livestock deaths may occur. Against a regional backdrop of internal conflict and political instability, there is a continuing flow of refugees, asylum seekers and internal displaced persons.

Most humanitarian disasters are overwhelmingly generated by political crises and armed conflicts but they geographically are not limited to conflict-affected areas. For these reasons, humanitarian crises and peace and security are highly intertwined. Access to humanitarian aid by those in need and access to the needy could be hampered by the security situation. Governance and respect for human rights play critical roles in preventing and addressing root causes of humanitarian crises and increasing humanitarian effectiveness. In this regard Member States and RECs as well as the AU need to speed up the bloc endorsement, ratification, domestication and effective implementation of the AU and international legal instruments, particularly the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, the African Charter on Election, Democracy and Good Governance, the African charter on Values and Principles of Public Service and Administration, and the African Charter on the Values and Principles of Decentralisation, Local Governance and Local Development.

CAP also emphasis the primacy of political leadership and governance in building an effective and inclusive global humanitarian architecture based on the principles of subsidiarity and complementarities in the construction of a global humanitarian architecture through decentralization of decision making and resource allocation that enables the first responders, local communities and local authorities to fend for their humanitarian affairs and for delivery of humanitarian aid. A unique call of the CAP is the localization of the humanitarian agenda by adopting concrete actionable recommendations and an adequate implementation mechanism fully reflecting the CAP to ensure the full realization of the Humanitarian Agenda. The new global humanitarian architecture needs to establish a conducive, global environment to ensure effective implementation, which includes mutually beneficial partnerships that ensure ownership, coherence and alignment of international support with local, national and regional priorities. For this reason, CAP aims to generate political will and international commitment, including resources mobilization for a global humanitarian agenda. The State bears the primary responsibility to protect and ensure security of all populations in need of humanitarian assistance.

Nuances of State Capability

The Capable State is the main driver of social and economic development and improved livelihoods. In this regard, States constitute the main drivers in assuring human security, perceived as the totality of what makes a human being secure in his or her surroundings and in the achievement of the vision under Agenda 2063 for Africa’s social and economic transformation. Preventive diplomacy could prove to be an efficient tool to prevent political crises that may transform into humanitarian crises. Addressing the governance deficit requires also sustaining the peace that prevailed and preventing it from collapsing again. In this regard, the role of Member States, RECs and relevant organisations is of paramount importance.

To achieve this goal, the CAP aims at building the following four capabilities of the state. Predictive capabilities as the first line of defence against humanitarian crises related to early warning, which is a function of scientific and communication capacity. Preventive capabilities as the second line of defence against humanitarian crises related to the proactive developmental early intervention that is the function of socio-economic capacity, pro-poor policy, governance with foresight and the application of the principles of subsidiarity at national and regional level through decentralization, devolution or federation. The CAP focuses on prevention is a key factor to mitigate the impact of humanitarian crises and is highly intertwined with the primary duty of the state.

Responsive capabilities as the third line of defence against humanitarian crises related to reactive intervention, including relief which is a function of socio-economic capacity, and governance for effective delivery of basic legitimately expected services to the population. CAP acknowledges the nexus between humanitarian action and development, humanitarian issues are development issues and there is no particular boundary between them. Thus, humanitarian action is not limited to relief. Rehabilitation and recovery are integral parts of the humanitarian action and should be accorded the necessary attention and sufficient resources. Therefore, humanitarian action should go beyond emergency response and be perceived as part of a long-term development, peace and stability strategy. As part of the state, the armed forces and need to be active in establishing mechanisms for the deployment of military assets as enablers in the humanitarian system without compromising humanitarian principles, the safety of humanitarian workers and related infrastructure.

Adaptive capabilities as the fourth line of defence against humanitarian crises related to the abilities and coping mechanisms of societies, communities, state and non-state institutions to ‘bounce back’ after facing adversity, shocks and changing environments. This capability relies on socio-cultural traits, social innovation, traditional structures such as the informal economy, small scale cross-border trade, cross-border spontaneous mobility and migration, and natural resources sharing.

Localization of Humanitarian Response

Building effective and sustainable humanitarian architecture is unthinkable without the active participation of national and local authorities and local communities. A more revolutionary approach of CAP relates to the reconceptualization of the ultimate aims of the humanitarian aid. CAP emphasis on institutional mechanisms need to be established at national and local level. As part of the implementation of the principle of subsidiarity, all actors at international, regional and sub-regional levels should support the national efforts, and the national authorities should serve as backups to local authorities and communities.

More importantly, it emphasizes that the global, regional or bilateral partnership has to be built on principles such as the principle of subsidiarity, (9) complementarity and mutual accountability.(10) It assumes Africa and its RECs have peculiarities with different resource endowments, priorities, challenges and needs. A global humanitarian system will not be able to offer a “one-size-fits-all” strategy. All levels of humanitarian systems could significantly benefit from a decentralized organizational plan. Proximity and local expertise would help tailor all interventions to local contexts. Furthermore, localization enhances ownership which encourages the initiation of programmes by local entities. But localization needs to capacitate local authorities to implement and discharge their responsibilities, as well as to mobilize traditional and modern civil society organizations such as faith-based institutions, community leaders, and the private sector.

Therefore, CAP urges for strict adherence to the principle of subsidiarity. The ultimate goal of subsidiarity is to enable states and local authorities to take responsibility for the humanitarian aid in their respective localities. Thus, all donors, UN, AU and for that matter RECs, would become a collective ‘back-up generator or subsidiary support system’ for national systems, which in turn would act as a back-up for local governance structures. The role of international actors, therefore, will not substitute national systems, but capacitate them. Localization of humanitarian system enhances community engagement and facilitates consideration of the peculiarities of each locality and community, civil society organization (such as youth and women association) and the private sector (transportation, hospitality, etc.) as well as the priorities of humanitarian disasters.

Such an approach enables Global Humanitarian Architecture to address peculiarities of each nation and region, including emerging issues such as the epidemic disease outbreak in Western Africa, cyclical drought and famine-like situations and localized violence amongst pastoralist communities in the Horn of Africa and Sahel region, flood related disasters in Southern Africa and the threat of terrorism in northern, western and eastern Africa. Thus, there is a need for the State to build local capacities, not only at the level of the State, but also at the level of local communities. Local populations must be seen as vital players within the entire humanitarian system. The role of the State remains subsidiary to the intervention by local communities, which are the first actors providing humanitarian assistance. This distribution of roles requires States to build the capacities of their local communities and give full effect to the role of social and traditional structures at the local level.

Thus, the African Union supported the effective implementation of the principles of subsidiarity and complementarity should constitute the basis for the new humanitarian architecture. Thus, the role of international humanitarian organizations as well as regional organizations remains subsidiary to the intervention by local communities, which are the first responders to humanitarian crises and need to be supported.

Solidarity and Burden Sharing

The CAP reinforces on the spirit of Pan Africanism and the principles of African shared values shall provide the foundations for the African humanitarian architecture. The African Solidarity Initiative shall galvanize African support to Member States in difficult situations.

While it emphasizes on the primary responsibility of Member States for the protection of populations in need of humanitarian protection, the CAP reasserts the key responsibility of the international community to share the burden of humanitarian aid. The international community must share the burden imposed on host countries in Africa and ensure more fair means of burden sharing globally, particularly in supporting such affected Member States to cope with the impact of refugees and IDPs. As they are bearing important financial and social burdens, in accordance with the principle of burden sharing, and on the basis of the real costs of that burden, host countries deserve regional and international assistance to help them in mitigating the impacts of their hospitality. The roles of host countries should be recognized as significant contributions to humanitarian assistance by properly communicating the value and quantifying the contributions of host governments and communities to humanitarian situations.

In line with these changes, the financing of humanitarian action is also rapidly changing. The cost of humanitarian action has surged, and due to the impact of the 2008 financial crisis and the migration crises in developed countries, available resources for humanitarian aid show a downward trend. Member States also allocated very little in their national budgets for humanitarian responses. Nevertheless, the roles of the armed forces, the informal and the private sector as well as receipts of remittances from the diaspora have steadily increased in favor of humanitarian responses. Technological advances have also made resources mobilization and financial transfers much easier and more accessible.

Recommendations

The Covid-19 pandemic proves that the current humanitarian system is too fragile characterized by challenges related to multilateralism, financial problems and lack of solid commitment to international burden sharing.

The ultimate goal of the Common African Position is to help African countries in addressing humanitarian crises including the fight against Covid-19 pandemics. Adapting the capability framework in the AU CAP remains relevant for responding to pandemics like Covid-19.

The first line of strategic capability is to predict number of infections using scientific modelling and communications for preparedness. The second refers to conducting preventive early interventions by applying WHO guidelines including distancing, frequent washing, and where possible and necessary, wearing masks. Not all infections can be prevented, in the current case response needs to include tracing, testing, and treating. The last, fourth strategic capability is to adapt to new local and global realities of life during and post Covid-19. Adaptation requires both resilience employing community assets sharing, traditional structures of support, socio-cultural traits, the informal economy, and social innovation. These strategic interventions require the same efforts and resources that are being diverted to fight Covid-19.The likelihood of Covid-19 pandemics triggering or accelerating conflicts is explored.

- The COVID-19 will also deflect resources and attention from hundreds of millions African including the 25 million individuals of concern in need of humanitarian aid.

- With donor countries trying to mobilize all their resources to fight COVID-19 in their jurisdictions and without ICU care in many parts, Africa will become the triage of this pandemic.

- The COVID-19 will also affect the social, economic, and even security and political aspect of the society including planned elections.

- The continent remains vulnerable to many disasters including locust plagues, drought and conflict induced humanitarian crises. Various stressors such as climate change, conflict etc will outpace any development efforts in post-Covid-19.

- The recent gains in the Sustainable/Millennium Development Goals (S/MDGs) including reductions in extreme poverty will be undermined, if not totally wiped-out.

- The pandemic will trigger or accelerate existing health and other humanitarian crises. With the economy under lockdown, humanitarian work could be seriously affected due to increased risks to aid workers.

- Central to both the challenges and solution is state capability and governance. African states have limited predictive, preventive and responsive capabilities to contain and mitigate such pandemics.